Bill Maples is a highly regarded director of outpatient wound centers. He and his wife, residents of the Galveston Bay area, enjoyed visiting Southwest Florida and its beaches. So like thousands of people who get a taste of life in our area, they decided to move here permanently.

He applied for a position at NCH Healthcare System, and they hired him. The next step: finding a place to live. “The more we talked to people around here, housing was an issue—even finding it,” he says. “We wanted to come to a short-term rental or lease to get to know the area before we bought a home. But coming in and finding a short-term lease wasn’t the easiest thing.”

Maples found few housing options at sky-high prices. “We found a short-term lease in the upper-$3,000-a-month range for a three-bedroom apartment,” he said. “It was complete sticker shock, but they allowed dogs.”

Maples is among the lucky ones. He is established in his profession and in his mid-40s, and he and his wife sold their home in Galveston and eventually used that money to purchase a home in Collier County. It was good news for NCH, a large employer that has hired nurses, wound care specialists, certified nursing assistants and other staff, only to lose them when the new hires can’t find a place to live. The result: They are short some 300 positions (See sidebar, “Companies building their own workforce housing,” page 60).

Stories abound of people accepting jobs in Collier County only to find they can’t afford to rent a one-, two- or three-bedroom apartment, much less buy a home. That newly hired employee ultimately informs the school district, police department or hospital they can’t accept the job after all.

Pricing out employees

Hospitals aren’t alone; the Collier County Sheriff’s Office and other major employers can’t keep employees, either. The high cost of housing has created a worker shortage in the Collier County School District, too. The district’s website lists 250 job openings, including bus drivers and other non-instructional support staff. But it sorely needs teachers.

“The Board of Education of Collier County schools is trying to hire 60 teachers right now,” says Joe Trachtenberg, chairman of the Collier County Affordable Housing Committee. “There are loads of teachers who want to live here, but they look for apartments and leave because they are priced out of the market.”

When Collier County Sheriff Kevin Rambosk told the Collier County Commission that his deputies had to live out of the county, the commission approved a pay raise to make rents reachable. The $40 million in raises took effect Oct. 1.

“Deputies have to commute from other counties to protect Collier’s citizens,” says an affordable housing official. “Before the raise, they made $40,000 to $45,000 a year. They are priced out of the housing market.” The sheriff’s website shows deputy trainee pay now starting at $49,505.

Lack of human infrastructure—the service people and providers of basic services—is a societal problem. A community without health care professionals, teachers, police, electricians, carpenters and other “human infrastructure” lacks basic services that make that community complete. Not enough teachers? Schools close. Understaffed emergency rooms? Poor health care. Not enough police? Higher crime rates.

Many of Collier’s workers commute from other counties where they have affordable homes. Exhibit A: I-75 during rush hour. The jobs-housing imbalance is so bad in Collier that 40,000 people—some 17.4% of the workforce—commute daily from outside the county. They don’t clog just I-75 South from Lee County, either. They come west across state roads 70 and 80, and into Naples down Alligator Alley. They come from Highlands County, Glades County, Miami-Dade County and affordable parts of Palm Beach County.

A plan unused

Collier County government officials can’t say they weren’t warned this was going to happen. In 2016, at the request of the Collier County Commissioners, the Urban Land Institute launched a broad study of the forces that make the county out of reach for so many professionals. The result: ULI’s Community Housing Plan to create a county in which people can afford to live where they work.

The 2017 report opens with this: “Collier County has a statutory obligation to provide housing for its current and anticipated population. First responders, health care professionals, teachers and others have been priced out of the housing market and have to commute long distances. A vibrant and sustainable community needs to accommodate its workforce so that those people who educate our children and save our lives can live near where they work if they choose.”

The institute warned Collier County officials years ago that its shortage of nurses, police, teachers, construction workers, service workers and other human infrastructure would only grow worse. Today, when a housing advocate declares that it should be possible for working people to live affordably and raise children in Collier County, he or she holds up a copy of the ULI housing plan.

Nearly every sector of the community was involved in creating the ULI report, from business leaders and chambers of commerce to developers and major employers. The housing plan was presented after 20 Affordable Housing Advisory Committee meetings, 30 housing subcommittee hearings and five public hearings held by ULI and county officials.

When it issued its report in 2017, the institute listed six core strategies and 35 recommendations that included increased wages for workers; building affordable apartments around commercial and light industrial centers; and streamlining affordable housing development by reducing review time for plans, landscaping, setbacks, etc.

A small sample of the suggestions include:

- Increase density from the capped 16 units per acre to 20-25 units per acre in certain areas.

- Create local development codes to suit dorm-room-sized apartments in desirable, walkable neighborhoods.

- Increase the deferral of annual impact fees from 10 years to 30 years.

- Provide housing opportunities in/near commercial job centers.

- Use the housing trust fund that Collier County already has but is not using. Use impact fees, density fees and other planning costs that can be used for affordable housing.

- Extend public transportation, bike lanes and other infrastructure to low-cost land where affordable housing can be built.

Though Collier defers impact fees for cheaper housing and uses other short-term solutions such as the Tenant Based Rental Assistance Program, the county commission is not interested in doing what is necessary to solve the affordable housing problem, said Trachtenberg of the Collier affordable housing committee.

“I think the Urban Land Institute did a terrific job outlining the problems in Collier County and the proposed solutions,” Trachtenberg says. “Most of those were not implemented. Collier County still has the highest impact fees in Florida. The result: Things are much worse today than they were five years ago.”

Forty nine year old math teacher writes equations during class.

Deferring impact fees

For instance, the present impact fee deferment holds back the fees for 10 years; Trachtenberg and his committee have asked impact fees be deferred for as long as the housing is affordable.

He also points to money that he says is just sitting there, ready to be used. In 2018, voters approved a 1% increase in the county’s sales tax. Of the $490 million it would raise, $20 million was to go toward land for affordable housing, Trachtenberg said. The commission has not yet agreed to write that check.

“One point irks me,” Trachtenberg says. “We are still unable to use the $20 million to the good of the affordable housing problem. The commission keeps telling us they’re working on it. If you ask the commissioners why they aren’t strongly advocating affordable housing, their answer [is], ‘Most people in Collier County are opposed to more development, especially this kind of development.’”

For example, the Collier commissioners in August discussed setting aside land in the mini-triangle for 114 more multifamily units to satisfy a growing population, but again, they will be priced at market rates. Trachtenberg criticized the decision.

“We are envious of the success Lee County has had with their affordable housing efforts,” he says. (See sidebar, “How Lee County is (was) doing it,” page 56).

Calculating what’s affordable

To measure the need for subsidized housing and spending on other social programs, municipalities begin by determining an area’s annual median income. According to the U.S. Federal Reserve, Collier County’s median income hit $81,895 in 2020. Two years later, the median income of an individual in Collier is closer to $92,000.

The Florida Department of Economic Opportunity says about 64% of Collier County jobs pay less than $33,250 a year—about $60,000 less than the county’s median income. At that salary, a worker spending half his salary on rent and utilities pays $1,385 a month for housing (rent and utilities). Under ULI’s guidelines, that worker is “severely cost-burdened” when it comes to housing. The median income does not include income taxes, social security and other deductions. When that’s accounted for, that leaves very little for car payments, gas, groceries and other expenses.

“If you make $50,000 like a cop or a teacher and you spend 30% on housing, you can only afford $1,300 a month rent,” Trachtenberg says. “There are few one-bedroom apartments in Collier for $1,300 a month. In Collier County, a two-bedroom is $3,000 a month, a three-bedroom, $4,000 a month.”

The economic opportunity office’s statistic—that 61.4% of Collier workers make $33,250 a year or less—also means that 61.4% of Collier workers cannot afford even a one-bedroom apartment in Collier County. The institute warned Collier County officials that 11,000 more apartments or homes will be too expensive for the 61.4% in the next decades.

Why housing is so expensive

Collier County’s gorgeous shoreline is home to some of the most valuable real estate in the nation. Its mansions and luxury resorts are attractive to wealthier Americans looking for a warm place to live, especially after the pandemic. Reading a book poolside is likely more inviting than spending a winter hiding from COVID-19 in a Pittsburgh or Baltimore apartment.

“People all over the country have various options when considering where they choose to live, and an increasing number continue to make Florida home,” says Lee County Commissioner Ray Sandelli. “As such, demand, as in any market, continues to drive prices up.”

Developers are in the business to make money for themselves or investors and have no incentive to build lower-cost housing when they can make such big profits building luxury houses and apartments. It costs about the same to build either. “The costs associated with development are similar,” Sandelli says. “Materials, labor and land have all seen notable increases due to such demand, which puts pressure on both buyers and the developers as all parties try to manage bottom lines and margins. Such pressures additionally make it increasingly difficult to meet the needs associated with the all-important workforce housing sector.”

Vacation rentals and other short-term lease agreements sent rents into the upper atmosphere, even before Hurricane Ian hit Southwest Florida and destroyed housing stock. The damage in Collier is far less than that suffered by Lee County, so construction projects quickly resumed at the level before the Sept. 28 storm.

Of note, the Florida Legislature forbids local governments from regulating how much owners can get for rent, but the Collier County Commission did pass on first reading an ordinance that would require Collier landlords to give 60-day notice when raising rents more than 5%. It is expected to pass on second reading.

That doesn’t mean landlords won’t charge what they can get for rent.

“Airbnb has been a destructive force in this market,” Trachtenberg says. “It’s not rare to see a waterfront house on Aqualane Shores rent for $100,000 a month. If people can rent their house out for $30,000 a month for January, February and March, why should they rent it out to a teacher for $1,000 a month?”

The human infrastructure shortage is not unique to Southwest Florida; ensuring there’s enough affordable housing in a community has become a professional specialty for city managers. Dan Rosemond is a former city manager who developed affordable housing in Indian River County and other Florida communities. He said municipalities rely on complex plans such as ULI’s when fashioning future communities.

“Managing growth and development is a formula-driven world,” Rosemond says. “The question that municipalities have to ask themselves is, ‘What efforts are they going to make to attract those people to live in the immediate geography?’ To have quality schools or adequate levels of service, you have to have housing they can afford. Either they won’t work in that location, or they’ll have to commute from a place they can afford.”

How Lee County is (was) doing it

Collier County’s affordable housing advocates may blame county leaders for not tackling affordable housing shortages, but in Lee County, things are different. Elected officials are on board with incentives and funding, while many residents oppose giving too many breaks to developers.

Gulfshore Business spoke with Lee County leaders to see how they’re using federal grants and developer incentives to spur more affordable housing. Here are some of the incentives Lee County offers in its Local Housing Assistance Plan:

- Expediting approval of development orders, permits and other requirements for affordable housing projects;

- Waiving utility connection fees and other permit costs;

- Adjusting zoning densities so a portion of apartments or condos can be rented at below-market rates;

- Reserving infrastructure capacity for housing for very-low-income persons, low-income persons and moderate-income persons;

- Supporting development near transportation hubs and major employment centers, i.e. mixed-use developments; and

- Preparing a printed inventory of locally owned public lands suitable for affordable housing.

Lee County Commissioner Ray Sandelli, who sits on the Lee County Affordable Housing Advisory Committee, said he and other commissioners know affordable rents are vital to a self-sustaining community.

When Sandelli talks about affordable housing, he’s talking about taking care of people and families who want to live where they work.

“We on the Lee County Board of County Commissioners understand the importance of affordable housing costs and rents to create a self-sustaining community,” Sandelli says.

The county regularly funds workforce housing projects. In June, the county commission agreed to give $2.5 million from the American Rescue Plan Act to Habitat for Humanity. The money will pay for infrastructure (water, sewer, electric, etc.) to build more houses in Habitat’s McNeill neighborhood near Pondella and Pine Island roads.

In July, the commission agreed to use $7.5 million from its American Rescue Plan Act Recovery and Resilience Program for two affordable housing developments in Fort Myers.

Though Joe Trachtenberg, who chairs Collier County’s Affordable Housing Advisory Committee, says he is envious of Lee County’s workforce housing efforts, some Lee County residents are not so thrilled with their county’s efforts.

Neighborhood organizations including Women for a Better Lee have gone public with their complaints about Lee County’s affordable development incentive programs. Noting that the Florida Legislature in recent years has diverted $2.5 billion in affordable housing funds to other programs, opponents don’t like local taxpayers picking up the tab for impact fees, utility hookups, cheap land and other expenses they believe developers should pay. They decry the loss of mangroves in unincorporated areas where the county gives away prime land in exchange for promises of cheap housing.

The group points to the owner of an Estero apartment complex who was required to offer 63 affordable housing units in exchange for permission to build. The owner instead sold to another company for $90 million. He then paid the county $1.26 million for failing to build the affordable apartments as promised. The $1.26 million went into the county’s affordable housing fund for a project slated for Cape Coral.

Then came Hurricane Ian, which knocked all classes of housing off the market. To say it has exacerbated the affordable housing shortage in Lee County is an understatement. The latest damage estimates from Lee County’s Hurricane Ian Damage Assessment Map show that the storm eradicated 4,671 homes along Sanibel, Estero Boulevard, Fort Myers Beach and inland. Some 12,384 homes sustained major damage, which means some 17,000 homes may be uninhabitable for some time.

There are reports of extremely high jumps in post-storm rent. According to one apartment seeker who spoke to WINK News, Springs at Gulf Coast in Estero told her a two-bedroom, two-bath apartment was $2,301 a month. Two days later, the ask was $3,491.

There is unintended irony in all of this. Police, nurses and teachers are not the only human infrastructure professionals that can’t find affordable housing. Skilled tradesmen, such as heavy equipment operators, steelworkers, concrete workers, carpenters, roofers and electricians, also can’t afford the higher rents in Lee County. But they are exactly the workers Southwest Florida needs to rebuild its communities.

Companies building their own workforce housing

The human infrastructure/worker shortage has become so acute that some companies, such as giant medical device manufacturer Arthrex Corp., have warned Collier officials that lack of affordable housing makes it extremely difficult to hire and retain workers.

David Bumpous, senior operations director for Arthrex, told the commissioners in July 2019 that if they could not fix the problem, the company would move some of its billion-dollar business out of the county, possibly to spots in the Carolinas.

Many corporate employers—some of whom postpone opening a second or third location or reduce their hours of operation to avoid employee shortages—are finding other ways to retain workers tired of paying sky-high rents. Some companies are going as far as building housing for their employees.

“The problem is too serious to wait,” says Joe Trachtenberg, who chairs Collier County’s Affordable Housing Advisory Committee. “I’ve suggested to large employers that they find existing properties, such as schools and motels, that they can quickly convert into affordable housing.”

The Florida Hospital Association and the Safety Net Hospital Alliance said Lee, Collier, Charlotte, Manatee and other Florida counties were short 11,500 registered nurses and 5,600 licensed practical nurses in 2019. The numbers have not improved.

NCH Healthcare Systems, one of the region’s largest employers, has seen too many new hires change their minds when they can’t find an affordable apartment or house.

“We have more than 300 open positions,” says Jennifer Hart, director of talent management for NCH. “We’re actively looking to fill positions in administration, nurses, respiratory therapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists and clinical workers in physician’s offices. That has been the norm in recent years.”

Matthew Holliday, director of government relations at NCH, said the hospital shared its plight with the Collier County Commission and other local government officials.

“We told them anecdotally about the people who have accepted positions at the hospital, and when the new hires found out how much it cost to rent an apartment or condo, they declined the job,” Holliday says. “They looked at the cost of living here and realized they got more bang for the buck where they were living up north.”

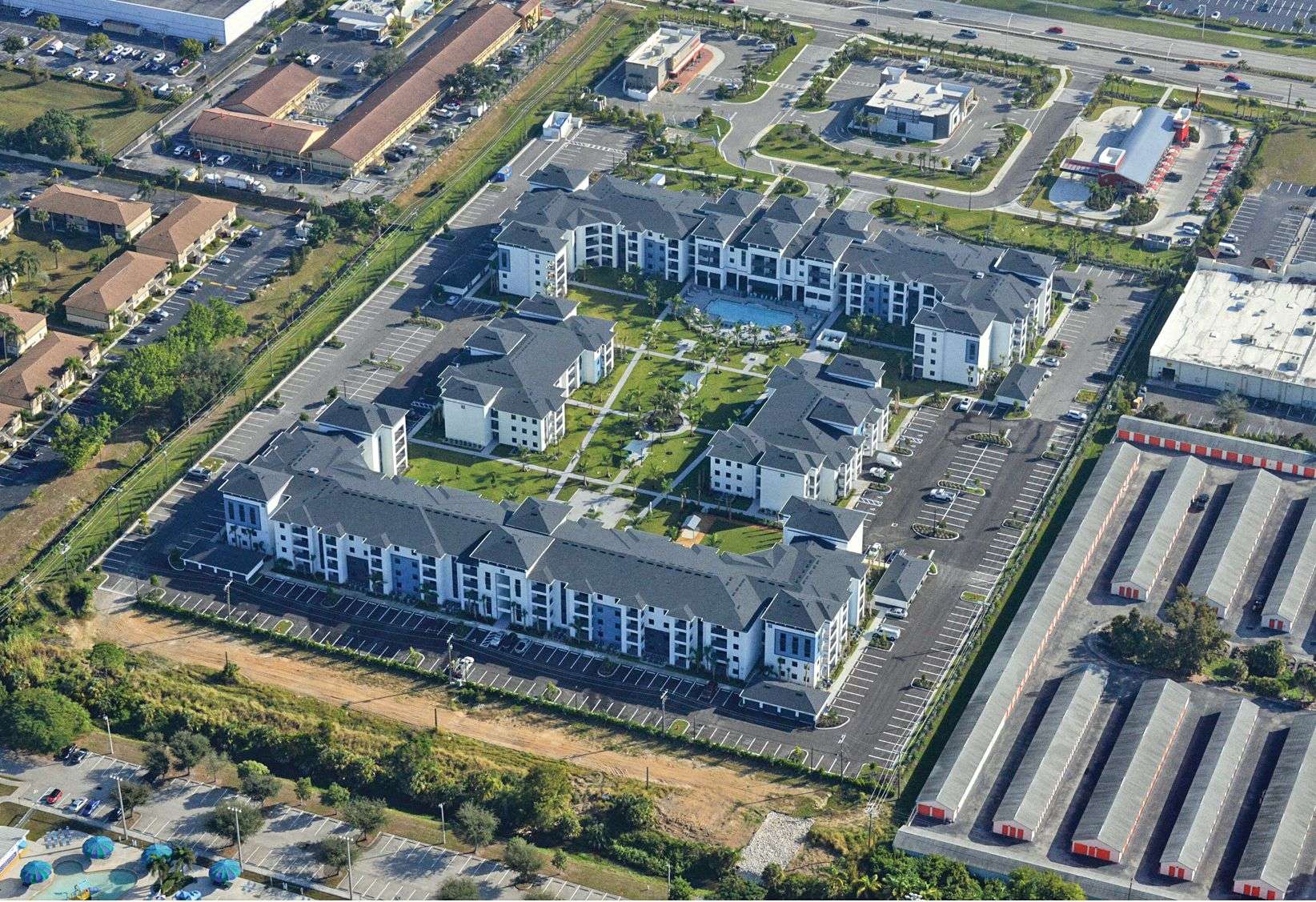

The hospital system is taking the bull by the horns: It is building affordable apartments of its own that new employees can move into upon hiring. It purchased a Super 8 motel and renovated it for employee housing.

“NCH Healthcare is building 20 fully furnished studio and efficiency apartments in close proximity to our hospital,” Hart says. “The monthly rental rate will be lower than fair market value, fully furnished and [with] amenities such as a pool, community living area, a community kitchen with utensils—people can move in right away.”

The project was finished in September as Hurricane Ian was building in the Atlantic. The Tollgate Apartments, as NCH dubbed its new housing, also served as a temporary hurricane shelter during Ian.

“The project never slowed down, and we were able to move the employees and families (children included) into the Tollgate Apartments on schedule,” says Hart. “In addition, NCH offered temporary housing in the apartments for those employees and their families deeply impacted by the hurricane.”

NCH also created a new Housing Coordinator position and put Nadine Fraser in charge. It is Fraser’s job to help new hires find rental apartments or houses on the open market. If the new employee accepts a job, the next step is to send them options for rental apartments and other available housing and contact numbers. Fraser talks to the rental offices to smooth the way.

“We partner with seven apartment complexes in Collier County who waive or discount application and administrative and other fees for our NCH employees,” Fraser says. “Those fees can be from $100 to $400.”

NCH is not the only large employer considering employee housing. Ryan Carter, president of Scotlynn USA Division Inc. and Scotlynn Transport LLC, last year completed a multimillion-dollar headquarters in the Alico Road and I-75 area. The international transport company is diversified and must maintain a large staff of skilled office and administrative workers.

Hurricane Ian did some damage to the headquarters, but Scotlynn employees are using the company’s resources to help the area recover.

The company’s plan for employee housing, however, has not slowed. “A month or so ago, we had two employees who made $42,000 a year and could not qualify for a two-bedroom. That’s crazy,” Carter says.

The company hires interns to provide a career path for young people, “but there is no short-term place for them to live,” Carter says. “The places don’t exist, so we got creative. Florida Gulf Coast University has dorms they don’t use in the summer. We put 20 folks there, but it’s a short-term solution.”

Here’s an idea that Lee County Ray Sandelli has suggested for the county that Carter likes: letting industrial parks, hospitals and other large business campuses overlay residential buildings onto their properties. Industrial and business campuses already are zoned for concentrated populations. Building residential units would not require more density, and that number of people would not strain existing utilities.

“If the government is able to be flexible with zones that are commercial and industrial, we have room to build a 20,000-square-foot building for housing entry-level employees,” Carter says. “That will allow new hires to live there in the first six months to a year of employment so they can build up some savings. It also provides a good, close-proximity place for them to work and live.”