For the last 50 years, Sanibel has leaned into an isolationist stance when it comes to the island’s commerce. And that’s served local business just fine.

This November, Sanibel marks 50 years since its incorporation. The island paradise has made a name for itself as an environment-focused sanctuary, distinct among the overly developed tourist hubs of this state. Compared to the chaos and noise of local unregulated tourism—before Hurricane Ian, nearby Fort Myers Beach routinely made lists for top spring break destinations—Sanibel has remained a tranquil haven. Its secret is that the island has kept its distance from big business and sprawling development, maintaining a focus on preservation.

“From a business standpoint, Sanibel has thrived because of this isolationist mindset,” says John Lai, president and CEO of the Sanibel and Captiva Chamber of Commerce. “There are very few places where people can find what we have, and this has played very well into the world-class destination we’ve become. We’re not just another Florida beach.”

A Land Apart

A Land Apart

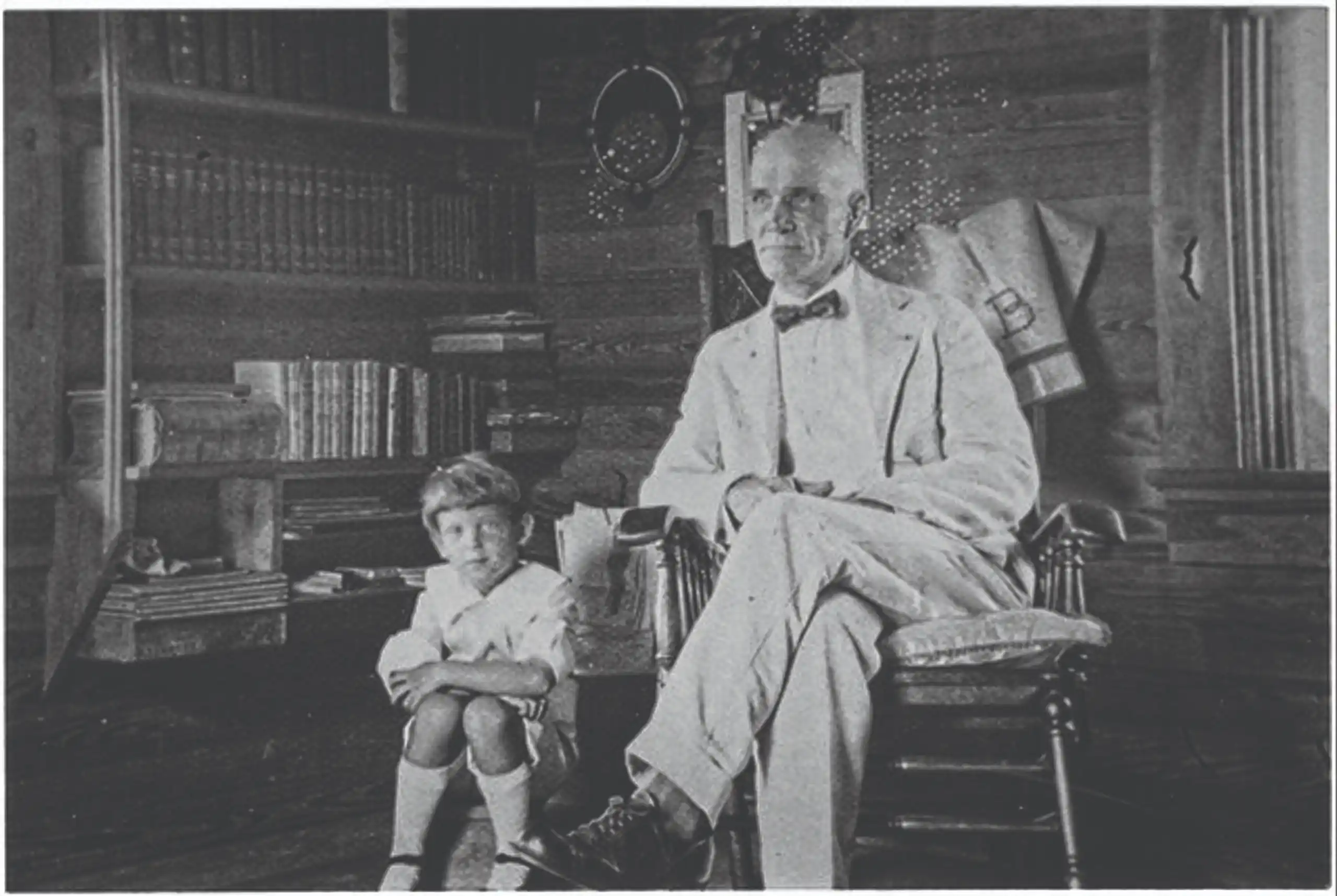

For decades after the first homesteaders put down stakes in the late 1800s, Sanibel remained a hard-to-reach barrier island off the coast of Lee County. Visitors arrived by private boat, and the majority of the island’s population was made up of year-round farmers who grew crops, such as grapefruit, watermelon and key limes. But when a pair of devastating hurricanes in the early 1920s wiped out the island’s agriculture industry, tourism quickly filled the void. A regular ferry service began running to Punta Rassa in 1928.

Still, life on Sanibel felt worlds apart from the mainland. There was just one shop—Bailey’s General Store—where residents and visitors would stock up on groceries for the week. Though most of the properties had well water, the sulfurous rotten-egg smell made it a bear for brushing teeth. Most families bought their drinking water at the store, too.

The island’s image as a sanctuary with an emphasis on unspoiled nature continued for several decades—but trouble lurked on the horizon. The surrounding areas were increasing in popularity, and developers were eager to transform the Florida landscape. As long as Sanibel remained separated from the rest of Florida, then it could preserve its island oasis feel. That abruptly came to an end in 1963 with the building of the original Sanibel Causeway, which connected the island to the mainland. Developers were eager to plant high-rise hotels and condominiums along Sanibel’s pristine shores, and the pro-growth Lee County Commission approved Sanibel for high-intensity urban development, including a four-lane expressway. The island’s population threatened to skyrocket.

“Almost overnight, the population changed so rapidly that the locals became a minority,” says Ty Symroski, president of the Sanibel Historical Museum & Village, whose family has been coming to the island since before ferry service started. But that minority was powerful. “We have a strong history of collaboration on this island,” Symroski says.

In the wake of the causeway’s construction, members of the Sanibel community banded together with a singular intention: to protect their sanctuary island from the grips of overdevelopment. In 1974, they were successful. The island incorporated, becoming its own city, capable of writing its chosen destiny. “We’re a community that knows how to work together,” Symroski says. “That’s part of what makes Sanibel so special.”

The Sanibel Plan

The Sanibel Plan

The first act of the newly incorporated city was to create the Sanibel Plan, a revolutionary land-use plan for governing the development of the island. The plan went into effect in 1976, putting nature at the center of all future plans and limiting development to a third of the island.

Despite accusations otherwise, the creators of the plan weren’t ignoring good business sense. In fact, they were dictating their own version of it. “Sanibel’s economic fortune is directly related to the viability of its natural systems,” the plan states. “Sanibel’s appeal as a pleasant place to live or visit is based upon vital wildlife, open beaches and a tranquil ambiance.” The plan’s authors knew that, in order for Sanibel to thrive, it would need to protect what made the island unique.

The Sanibel Plan was remarkable for its time, nearly unheard of in a state whose commercial history has depended on ceaseless land sales. Even more impressive, that plan has stayed intact over the last 50 years. Thanks to the plan, over two-thirds of the island has remained in conservation today. The key to its enduring success?

“It’s the personality of Sanibel,” says Thomas Ankersen, a professor emeritus at the University of Florida Levin College of Law, and director emeritus of the Coastal Policy Lab at UF’s Center for Coastal Solutions and the Florida Sea Grant Legal Program. He served as the first Pfeifer Conservation Fellow at the Sanibel-Captiva Conservation Foundation, and he lectures regularly on the Sanibel Plan. “The population on the island has a basic love for nature, and they want to maintain this place as a natural sanctuary. That has transferred from one generation to the next here, and even after the disruption of Hurricane Ian, it persists.”

McSpoiler Alert

McSpoiler Alert

But that’s not to say that the plan hasn’t gone unchallenged, or that Sanibel’s isolationist policies haven’t been put to the test. One of the biggest of those tests came in the early 1990s, when McDonald’s sought to build an eatery on the island. Local residents rose up in protest, and anti-McDonald’s bumper stickers appeared all over the island with the slogan “McSPOIL: No McDonald’s on Sanibel.” A Dairy Queen already existed on the island, and a Subway had managed to gain a foothold. But McDonald’s was going too far, local residents agreed.

By keeping big chains out, the island has allowed small, locally owned businesses to thrive. French bistro Bleu Rendezvous has gained a loyal following since it opened on Sanibel in 2015. Before that, the fine dining restaurant was located in Fort Myers under the name Bleu Windows Bistro in the space currently occupied by Harold’s. Husband and wife owners Mari and Christian Vivet dreamed about moving their white-table-cloth establishment to one of the local islands, either Fort Myers Beach or Sanibel. Ultimately, Sanibel won, in large part because of the island’s isolationist approach to commerce. “Business-wise, it made more sense,” Mari Vivet says. “It has that exclusivity.”

This fall, after nearly a decade on the island, the Vivets sold Bleu Rendezvous to a French couple. As they work to create a seamless transition to the new ownership, they are optimistic about the restaurant’s continued success. This optimism stems from the way Sanibel businesses countered the devastation of Hurricane Ian. Bleu Rendezvous was one of the first restaurants to reopen after the storm. “We worked our butts off to get this place opened,” Vivet says. And they weren’t alone. “The storm brought the island businesses together for the common goal of getting people back on the island.” That kind of unified front was possible because many of the businesses on the island were owned by locals such as the Vivets. Going forward, they believe this will continue to serve the new owners well.

“This is a great time for businesses on the island,” Vivet says. “Sanibel is coming back. It won’t happen overnight—the hurricane was devastating for all of us—but there’s a momentum on the island.” And the new owners, she says, are motivated. “They want to carry on the traditions we started here.”

A Bright Future

A Bright Future

Since Hurricane Ian, the Sanibel and Captiva Chamber of Commerce has seen a remarkable outpouring of support for the island and its business community. But challenges still remain.

“Our biggest challenge is the wait for the return of most of our lodging units. We are currently sitting at just over 26% on Sanibel and 61% on Captiva with a combined 36.6% of our pre-Ian inventory,” says Lai. “That’s truly amazing, as we know that each unit is now in brand-new condition, but when you compare the inventory of hotel rooms pre-Ian at 30% and the number of nonaccommodation businesses reopened at 83%, we know that the off-seasons will be our biggest hurdle for the next couple of years.”

Businesses on the island have had to become more resilient over the past 50 years, Lai said. “In the past eight years alone we’ve seen several hurricanes including a direct hit by a Category 5, a red tide/blue-green algae event and a pandemic. However, in those same eight years we’ve seen record visitation, the end of just one peak season and a younger, more diverse resident base that spends more time on the island. Businesses that thrive tend to understand that we are not only a world-class vacation destination, but also that Sanibel is and shall remain a barrier island sanctuary. The Sanibel Plan is our playbook that outlines a lot, but specifically that roughly 68% of our land remain in conservation, that our beaches shall remain natural and that formula retail is not allowed—which keeps the focus on small, locally owned businesses, and needs to be embraced. It truly sets us apart from any other vacation destination in our state.”

Despite the setbacks, Lai remains optimistic. He believes the future is incredibly bright for Sanibel’s island community. “In two years, based on the economic outlook that we have partnered with Florida Gulf Coast University and Charitable Foundation of the Islands to execute, our lodging units will be over 85% back online and every unit will be brand-new,” he says. “That rising tide will inevitably float all boats. We will see increased real estate transactions, plus retail, restaurants and attractions will thrive. We will be a community that is built back stronger than ever from every aspect.”