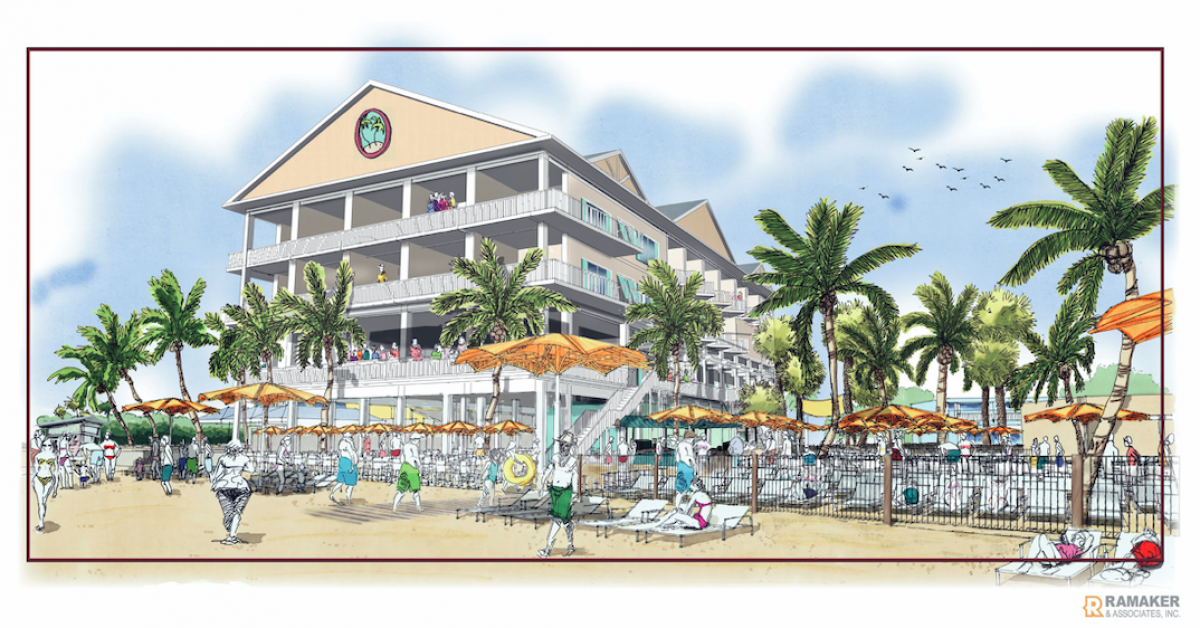

Lead Photo: Renderings of Margaritaville Beachside Suites.

Picture this: A sunny afternoon in Margaritaville, a frozen concoction in your hand, a Jimmy Buffett song stuck in your head and the beautiful Gulf waters just steps away.

Go lounge by the pool, grab dinner at one of the restaurants or just take the skywalk back to your room to sit and watch the sunset from the balcony. You’ll just have to picture it for now. It’s not quite reality; not just yet.

Right now, reality is the vacant buildings and empty lots on the north end of Fort Myers Beach where the Margaritaville Resort is supposed to go.

The resort should be done by now, the developer laments. Instead, it’s been years of debate and lawsuits, hard feelings and small-town politics. And don’t forget a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic.

The controversy surrounding the resort has galvanized the town of Fort Myers Beach regarding what to do about those 7 acres of land near Times Square, one of the most popular tourist destinations in Southwest Florida. Some see it as revitalizing the north end of the island. Others see traffic snarls, noise pollution, parking woes and the further erosion of a once-peaceful beach community. “It’s completely energized the community in ways I didn’t think were possible,” says Fort Myers Beach Chamber of Commerce President and CEO Jacki Liszak.

Margaritaville resort lobby

THE LAY OF THE LAND

Tom Torgerson first started visiting Fort Myers Beach in 1991. The Minnesota native loved the laid-back, non-pretentious vibe, and moved there full time about eight years ago. He liked going on long walks, and while he was out, he’d come across large parcels of land on the north end of the island with small beach shops and other businesses, some of which were falling into neglect. Tourists were flocking to Times Square and the nearby hotels and restaurants. So, he asked himself, why hasn’t anyone redeveloped these parcels? It’s a question many have probably asked themselves, but Torgerson actually had the means to do something. He’s the chairman of TPI Hospitality, a developer of hotels and restaurants in Minnesota and Florida.

In 2014, he started seeking answers to his question. He met with then-Mayor Anita Cereceda. He learned that several developers had tried to do something with the area, but nothing had ever broken ground. He attended a redevelopment meeting the town hosted, just to listen, and started formulating a plan.

His company began acquiring property in late 2014, eventually buying close to $30 million worth. Then he proposed an idea to the community about what to do on that property, which he called Grand Resorts. Three hotels. A big parking garage. A giant seawall.

“The community didn’t like it—that’s being polite,” he says now with a laugh. The outcry was loud and persistent: Grand Resorts was too grand. “That process really helped with our understanding of the area,” says Torgerson. “People here are very passionate.”

So Torgerson started over. For six months he met with two groups: the most vocal opponents of the Grand Resorts, and the island’s business owners. What would become Margaritaville started coalescing as a resort with dining and entertainment options. The new proposed development went through nearly 14 months of fine-tuning with the town government. They continued to chip away at the size, eventually reducing it to 254 rooms—less than half of what was previously discussed. Most of those rooms would be placed in the building off the beach, so as to not block any Gulf views as visitors came onto the island over the Matanzas Pass Bridge. To alleviate parking concerns, he proposed placing employee parking in an off-island lot on a parcel he owned that would eventually also feature a hotel and affordable housing. He also agreed to give the town a parcel near the bridge; the town council, which saw those and many other concessions as appropriate given the scope of the project, planned to landscape it and place a welcome sign. The development would still be big—bigger than what the current zoning dictated, but, as council saw it, the overall benefit to the community was even bigger.

The May 21, 2018, town council meeting was packed with residents. It would last about five hours, most dedicated to public comment and debate over TPI’s proposed resort. In all, 27 people commented, most in favor but a few opposed.

A woman took out a sheet of paper to read as she approached the dais. She introduced herself as Christine Patton, a familiar name to many on the island. She lived on Primo Drive, a quiet dead-end road across a canal from the development. Her family moved to Fort Myers Beach in 1958, she said. She and her husband bought their modest home on Primo Drive in 1977. “I’ve accepted lots of changes over the years, mainly the increase in population. Who wouldn’t want to live in paradise? But paradise is being threatened,” she told council. Even with the concessions, she said, the resort was too big for the area to handle. It violated town code, in her view, and it would set a bad precedent for future development. She noted the irony of the council backing such a big project; when Lee County approved the DiamondHead resort in the 1990s, residents banded together to incorporate the town so something so large could never happen again.

Nearly 40 minutes after she spoke, a man approached the dais and said his name even though everyone was quite familiar with him: Robert Conidaris, owner of the Lani Kai.

The Fort Myers Beach landmark’s image as “party central” attracts legions of tourists but also draws the ire of some neighbors who see the drunken rowdiness that often comes at the end of those parties. The Lani Kai would be neighbors with the new resort. Unlike Patton, Conidaris spoke off the top of his head, and wasn’t exactly cordial. Referring to council as “you people,” he called the parking situation on the island “the worst I’ve seen it” in the 40 years he’d owned his hotel. If the development passed, he said, “I promise you, everybody will sue you.”

Council passed the measure 5-0.

Just a few weeks later, Torgerson announced the development would officially be a Margaritaville-branded resort with its Buffett-themed accouterments. TPI would continue to own and operate the resort. Construction was scheduled to start that December … but then the lawsuits hit.

LandShark Bar & Grill

SEE YOU IN COURT

In August, Chris Patton filed two lawsuits in the 20th Judicial Circuit Court against the town, seeking to overturn the approval of the development. (One suit was eventually dropped.) Represented by Cape Coral attorney Ralf Brookes, who had previously represented the Lani Kai’s Conidaris in a suit against the town over a parking matter, Patton argued the development was unlawful on a number of counts. But the main point of contention came over the size and density of the development— and the procedure in which the town approved it.

Patton contended that the resort was out of line with the town’s comprehensive plan, which guided its land development code. According to her suit, the resort should have been approved for no more than 84 rooms according to existing allowances for density and limited at three stories instead of four. It also was approved for more commercial space than allowed and didn’t adequately meet parking requirements, the lawsuit claimed.

The key phrase in the whole process became “exceptional circumstances.” The town code does allow for deviations if a development proposes “exceptional circumstances” that can benefit the public. In this case, a new resort that could revitalize prime parcels on the island would qualify for “exceptional circumstances” given that it would not overwhelm the area surrounding it, according to the town’s response to the suit.

Plans to start construction were put on hold. And, over the two years it took for the case to make its way through court, only a few buildings would be razed.

While his name wasn’t on the lawsuit, the fingerprints of Conidaris were all over it. In fact, he told the News-Press that he was financially backing the suits. He’d later maintain publicly that he wasn’t against Margaritaville—just the size of it. Torgerson felt that the Lani Kai owner was trying everything he could to sabotage the development by essentially delaying it to death. (Neither Conidaris nor Patton could be reached for comment.)

About a year after the suit was filed, Judge Alane Laboda ruled in favor of the town, saying the “exceptional circumstances” guidelines were met. Patton quickly appealed to the state appeals court in Lakeland, which meant development would be on hold for months—possibly more than a year.

As the suits dragged on, Margaritaville continued to serve as a hot button topic in the community. Yard signs supporting the development popped up around town. Meanwhile, the 2020 council race was dragged into the fray. Mailers went out harshly criticizing incumbents Dan Allers and Bruce Butcher over their support of “big developers.” Another mailer proclaimed that the development posed a threat to endangered sea life. (Allers was re-elected, Butcher was not). Torgerson now says the positive reinforcement he got from supporters helped through those years. “If we didn’t have community support, we would have gone our merry way,” he says.

Mayor Ray Murphy

After a delay in the appeal due to the coronavirus pandemic, the justices in July let the lower court’s ruling stand. Then, a day later, Brookes filed another lawsuit in the circuit court. This time, Patton claimed the process used to approve the resort was unconstitutional. The town and TPI prepped for another lengthy court battle, but what came next was unlikely and tragic, and served as a turning point in the whole affair.

Shortly after midnight on July 15, 22-year-old Johnny Jackson was shot and killed outside the Lani Kai. Two other people were wounded in a spray of gunfire.

The shooting released a wave of anger in the community, much of it aimed at the Lani Kai and its ownership. Close to 20 residents commented at the next council meeting, many lumping the shooting and other crime at the Lani Kai in with the lawsuits and the delays in building Margaritaville. A few even questioned whether the Lani Kai could be countersued to recoup the money lost defending the development in court.

Two days later, the lawsuit was dropped. Mayor Ray Murphy and chamber president Liszak had been quietly meeting with the Conidaris family, Patton and others involved in the lawsuits to try to finally bring the issue to an end. Essentially, a lot of money and energy were being spent on court battles rather than other matters. “I appealed to their better business judgment,” Murphy now says.

Rendering of Margaritaville Resort’s JWB Bar & Grill

FUTURE DEVELOPMENTS

Torgerson is ready to move forward but isn’t ready to declare a grand opening date yet—he’s in the process of looking for another investor for the project. In the time of COVID-19, financing for resorts has been tight.

—Jacki Liszak, Fort Myers Beach Chamber president and CEO

Liszak is hopeful construction could still be on track to start soon. The island’s hospitality-based economy has suffered mightily and will be in need of more jobs and more tourism dollars. She sees Margaritaville spurring more redevelopment on the island and off. “I’m a big believer that a rising tide will lift all boats,” she says.

Margaritaville will be coming as the town has several other projects underway, including multimillion-dollar plans to refresh Times Square and Bayside Park on the north end. Estero Boulevard has also been undergoing major roadwork for the last four years, and will feature new drainage, sidewalks and landscaping once complete. “Fort Myers Beach is going to be taking some major steps forward,” Murphy says.

In 1995, Christine Patton, then an account executive with the Fort Myers Beach Observer, compiled a hardcover book titled A Pictorial History of Fort Myers Beach, Florida. In the intro, there’s a black-and-white photo of an unnamed gentleman walking along an idyllic beach with nothing else in sight except the ocean. Patton writes: “If this early beach stroller of Crescent Beach could only see what the future holds for this precious little strip of sand! In just a micro-second on the grand scale of time, Crescent Beach would become Fort Myers Beach on Estero Island, complete with high-rises, traffic snarls and the usual high-tech problems associated with the 1990s. Just think of what is to come!”

WHAT IS MARGARITAVILLE?

You know the song. But what about the hotels, restaurants and casinos?

Margaritaville is no longer just a catchy Jimmy Buffett song, but a global lifestyle brand. The singer had branched out into the brand back in the 1980s with a retail shop, and growth came quickly thereafter. It includes the dining, lodging, residential and entertainment locations, along with products: clothing, beach gear, a margarita mix (obviously) and more. Margaritaville found a way to brand just about anything with an island vibe. Variety reports the company brings in revenue between $1.5 billion and $2 billion a year.

There are 22 Margaritaville resorts in five different countries. The Fort Myers Beach location would be one of many the company is looking to open and will also feature Margaritaville-themed restaurants such as LandShark Beach Club and 5 o’clock Somewhere Bar & Grille. “The Times Square section of Fort Myers is known for its great food, entertainment and fun—attributes that are synonymous with Margaritaville,” says Margaritaville CEO John Cohlan in a statement.

TPI chairman Tom Torgerson said brand representatives approached him about a partnership. “[Margaritaville] has a great island vibe,” he says. “It’s a young brand, but it’s done exceedingly well. It’s a perfect fit for us.”